Items

Contributor is exactly

John Crawford

-

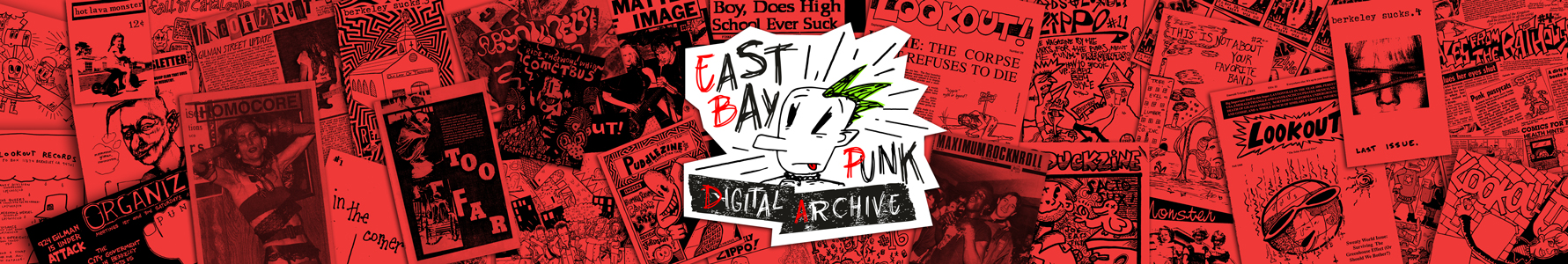

Twisted Image #8: Businessman Special Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies).

Twisted Image #8: Businessman Special Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies). -

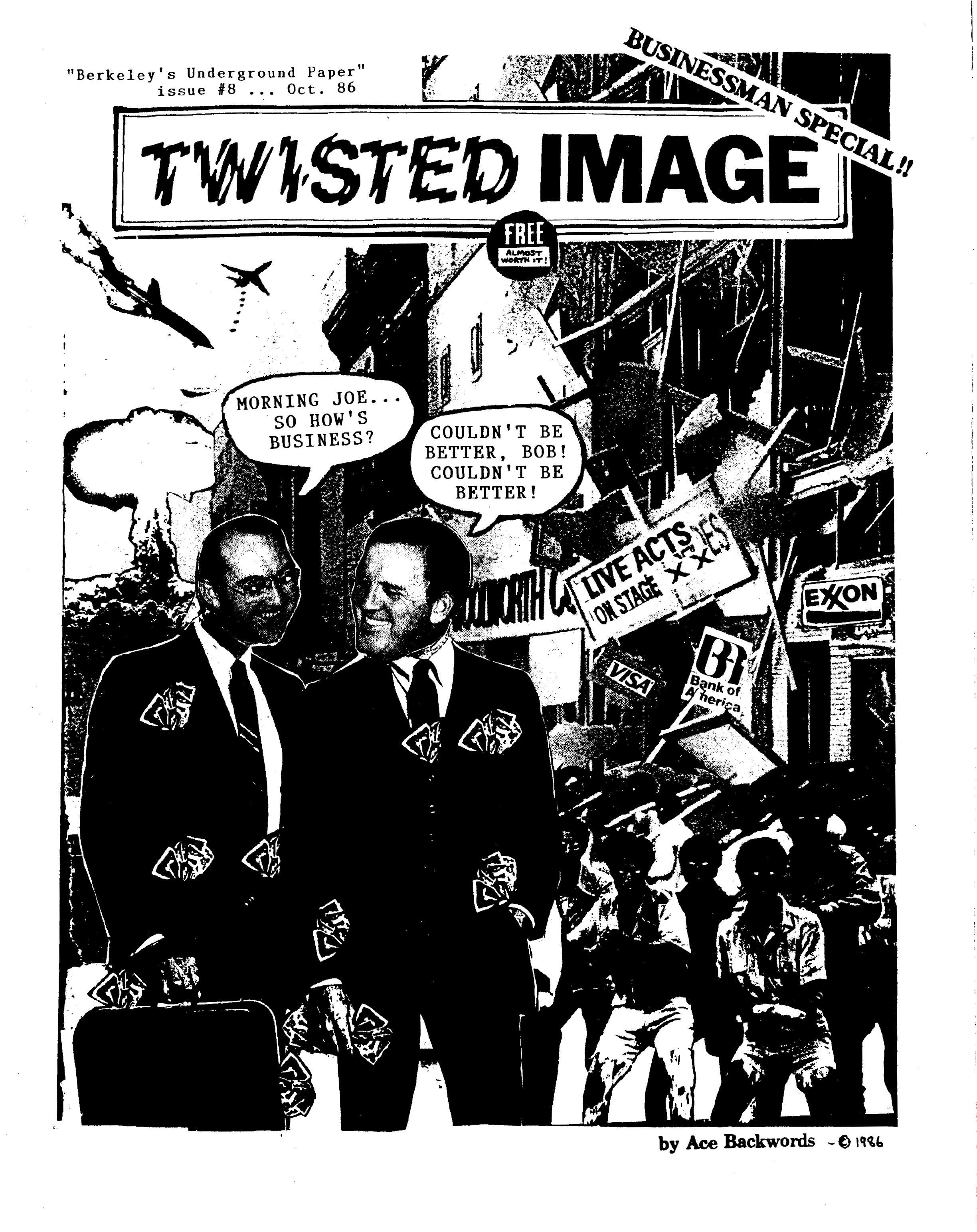

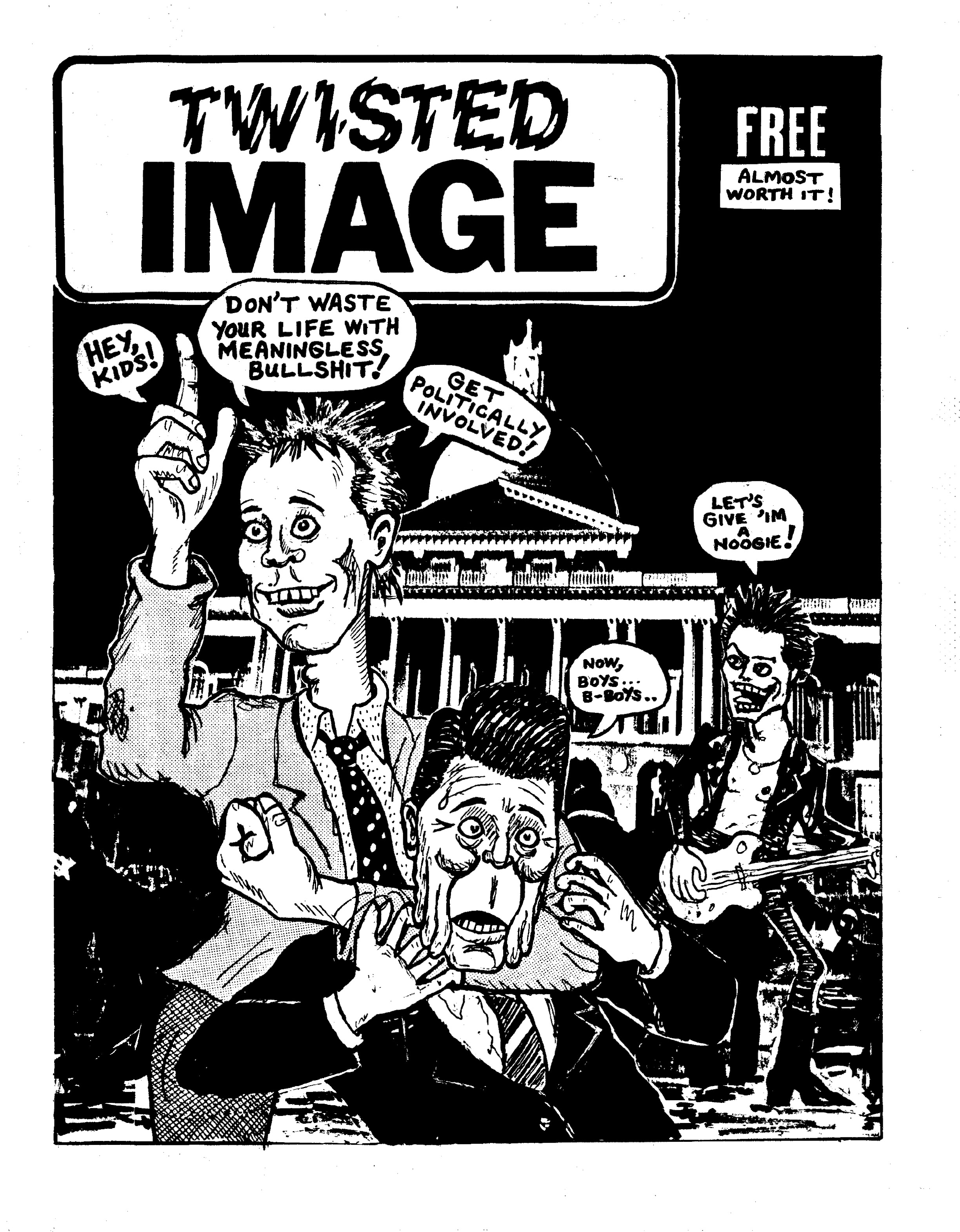

Twisted Image #6: Special Comix Art Issue Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies).

Twisted Image #6: Special Comix Art Issue Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies). -

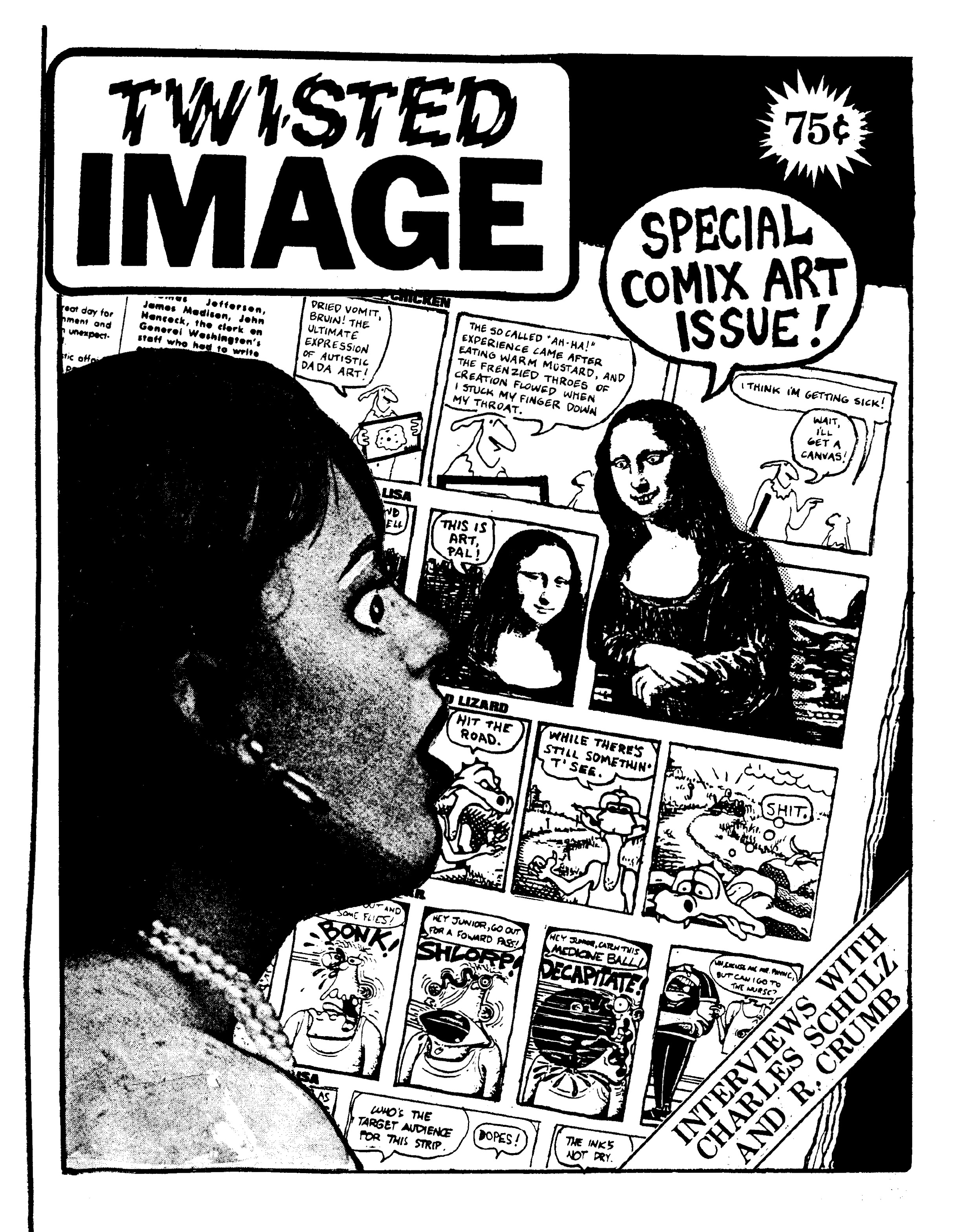

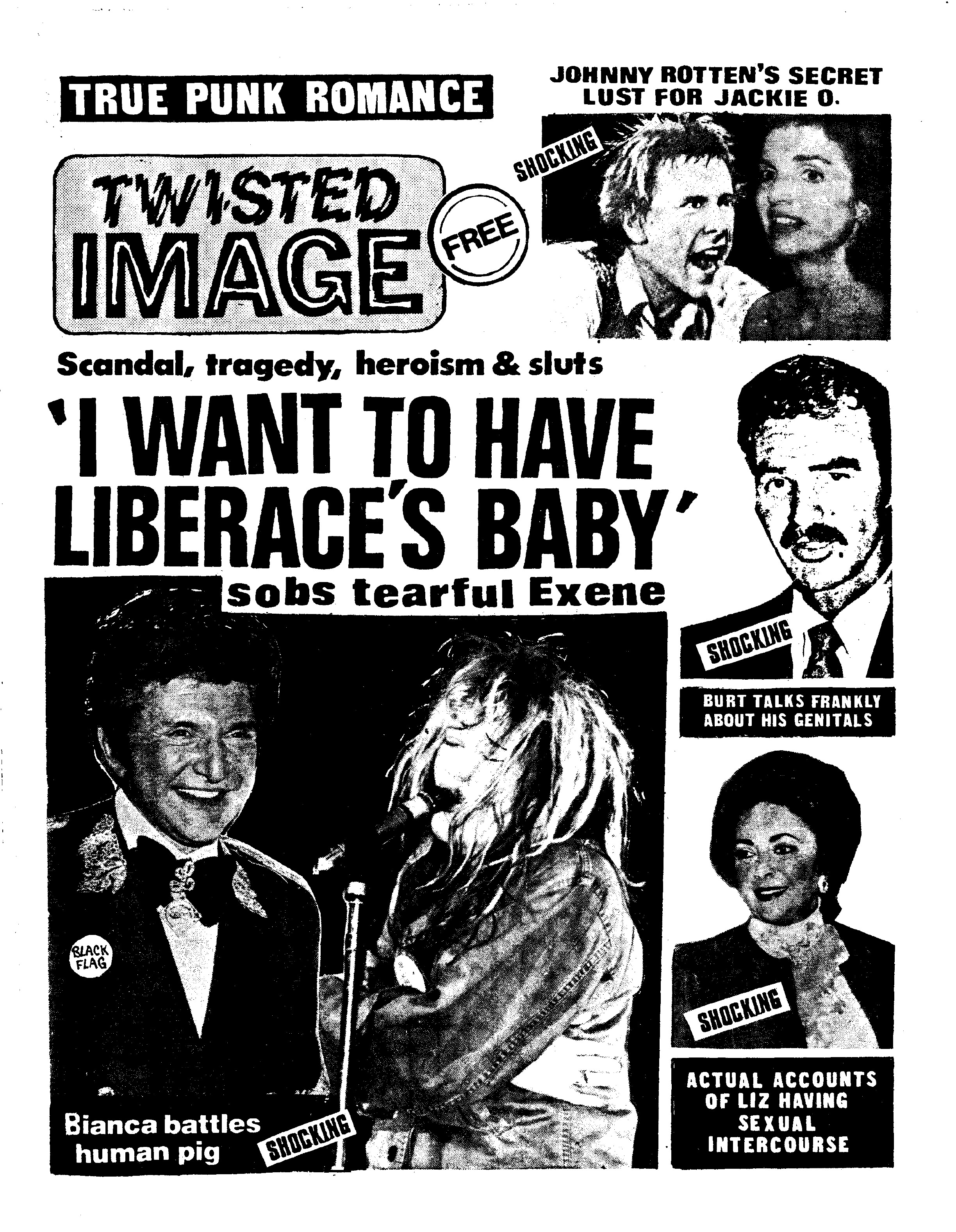

Twisted Image #5: Special Gore and Violence Issue Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies).

Twisted Image #5: Special Gore and Violence Issue Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies). -

Twisted Image #3 Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies).

Twisted Image #3 Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies). -

Twisted Image #2 Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies).

Twisted Image #2 Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies). -

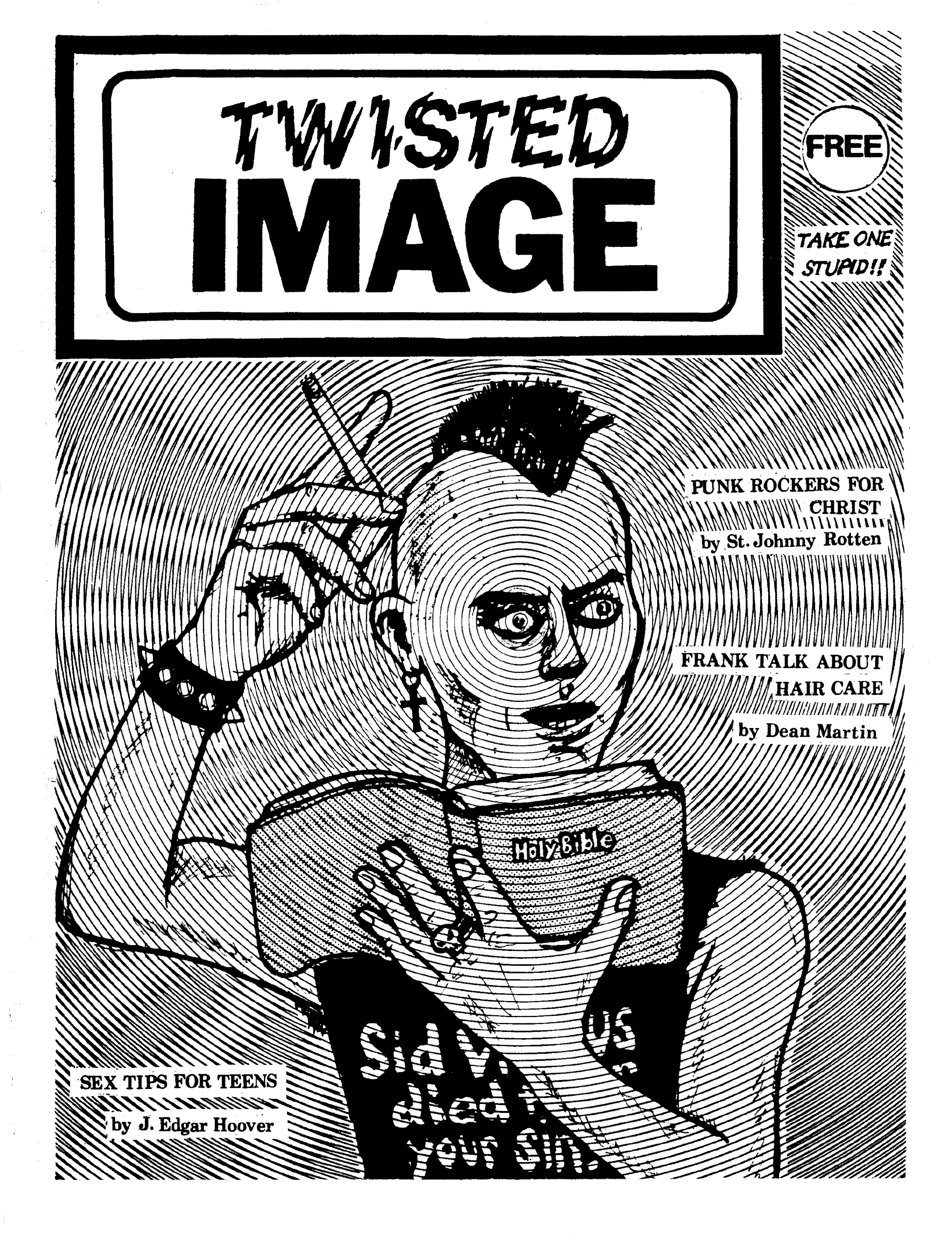

Twisted Image #1 Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies).

Twisted Image #1 Twisted Image was a zine edited by Ace Backwords (and later co-edited with Bruce N. Duncan and Mary Mayhem) between 1982 and 1994. The early issues of the zine (with a circulation between 5,000 and 10,000) explore different aspects of the punk rock youth culture that was increasingly making its way across the San Francisco Bay Area. They feature record reviews, interviews, visual arts, comics, and sarcastic critiques of the political discourses of the time. In 1987, Ace changed the format of the zine from a tabloid to a monthly xeroxed newsletter mostly focused on comics that he continued publishing until 1994 (with a circulation of 500 copies). -

Lookout #40 Lookout magazine started as a xeroxed community newsletter when Lawrence Livermore lived on Spy Rock, just a few miles north of Layonville, CA. Spy Rock was part of a constellation of locales across Mendocino and Humbdolt County that, since the late 1960s, had become increasingly popular among artists, hippies, and back-to-the-landers. Initially crafted in his solar-powered home, not far from the Iron Peak Lookout Tower, from which the magazine takes its name, the magazine engaged with local politics and tackled issues as diverse as environmental issues and countercultural philosophy. Over the years, following Livermore’s involvement with the Gilman Street Project in Berkeley and the punk-rock scene that loomed around it, Lookout’s focus shifted to music, which resulted in finding a whole new audience in the Bay Area and across the United States, especially among Maximum Rocknroll readers.

Lookout #40 Lookout magazine started as a xeroxed community newsletter when Lawrence Livermore lived on Spy Rock, just a few miles north of Layonville, CA. Spy Rock was part of a constellation of locales across Mendocino and Humbdolt County that, since the late 1960s, had become increasingly popular among artists, hippies, and back-to-the-landers. Initially crafted in his solar-powered home, not far from the Iron Peak Lookout Tower, from which the magazine takes its name, the magazine engaged with local politics and tackled issues as diverse as environmental issues and countercultural philosophy. Over the years, following Livermore’s involvement with the Gilman Street Project in Berkeley and the punk-rock scene that loomed around it, Lookout’s focus shifted to music, which resulted in finding a whole new audience in the Bay Area and across the United States, especially among Maximum Rocknroll readers. -

Lookout #39 Lookout magazine started as a xeroxed community newsletter when Lawrence Livermore lived on Spy Rock, just a few miles north of Layonville, CA. Spy Rock was part of a constellation of locales across Mendocino and Humbdolt County that, since the late 1960s, had become increasingly popular among artists, hippies, and back-to-the-landers. Initially crafted in his solar-powered home, not far from the Iron Peak Lookout Tower, from which the magazine takes its name, the magazine engaged with local politics and tackled issues as diverse as environmental issues and countercultural philosophy. Over the years, following Livermore’s involvement with the Gilman Street Project in Berkeley and the punk-rock scene that loomed around it, Lookout’s focus shifted to music, which resulted in finding a whole new audience in the Bay Area and across the United States, especially among Maximum Rocknroll readers.

Lookout #39 Lookout magazine started as a xeroxed community newsletter when Lawrence Livermore lived on Spy Rock, just a few miles north of Layonville, CA. Spy Rock was part of a constellation of locales across Mendocino and Humbdolt County that, since the late 1960s, had become increasingly popular among artists, hippies, and back-to-the-landers. Initially crafted in his solar-powered home, not far from the Iron Peak Lookout Tower, from which the magazine takes its name, the magazine engaged with local politics and tackled issues as diverse as environmental issues and countercultural philosophy. Over the years, following Livermore’s involvement with the Gilman Street Project in Berkeley and the punk-rock scene that loomed around it, Lookout’s focus shifted to music, which resulted in finding a whole new audience in the Bay Area and across the United States, especially among Maximum Rocknroll readers. -

Lookout #38 Lookout magazine started as a xeroxed community newsletter when Lawrence Livermore lived on Spy Rock, just a few miles north of Layonville, CA. Spy Rock was part of a constellation of locales across Mendocino and Humbdolt County that, since the late 1960s, had become increasingly popular among artists, hippies, and back-to-the-landers. Initially crafted in his solar-powered home, not far from the Iron Peak Lookout Tower, from which the magazine takes its name, the magazine engaged with local politics and tackled issues as diverse as environmental issues and countercultural philosophy. Over the years, following Livermore’s involvement with the Gilman Street Project in Berkeley and the punk-rock scene that loomed around it, Lookout’s focus shifted to music, which resulted in finding a whole new audience in the Bay Area and across the United States, especially among Maximum Rocknroll readers.

Lookout #38 Lookout magazine started as a xeroxed community newsletter when Lawrence Livermore lived on Spy Rock, just a few miles north of Layonville, CA. Spy Rock was part of a constellation of locales across Mendocino and Humbdolt County that, since the late 1960s, had become increasingly popular among artists, hippies, and back-to-the-landers. Initially crafted in his solar-powered home, not far from the Iron Peak Lookout Tower, from which the magazine takes its name, the magazine engaged with local politics and tackled issues as diverse as environmental issues and countercultural philosophy. Over the years, following Livermore’s involvement with the Gilman Street Project in Berkeley and the punk-rock scene that loomed around it, Lookout’s focus shifted to music, which resulted in finding a whole new audience in the Bay Area and across the United States, especially among Maximum Rocknroll readers. -

Lookout #37 Lookout magazine started as a xeroxed community newsletter when Lawrence Livermore lived on Spy Rock, just a few miles north of Layonville, CA. Spy Rock was part of a constellation of locales across Mendocino and Humbdolt County that, since the late 1960s, had become increasingly popular among artists, hippies, and back-to-the-landers. Initially crafted in his solar-powered home, not far from the Iron Peak Lookout Tower, from which the magazine takes its name, the magazine engaged with local politics and tackled issues as diverse as environmental issues and countercultural philosophy. Over the years, following Livermore’s involvement with the Gilman Street Project in Berkeley and the punk-rock scene that loomed around it, Lookout’s focus shifted to music, which resulted in finding a whole new audience in the Bay Area and across the United States, especially among Maximum Rocknroll readers.

Lookout #37 Lookout magazine started as a xeroxed community newsletter when Lawrence Livermore lived on Spy Rock, just a few miles north of Layonville, CA. Spy Rock was part of a constellation of locales across Mendocino and Humbdolt County that, since the late 1960s, had become increasingly popular among artists, hippies, and back-to-the-landers. Initially crafted in his solar-powered home, not far from the Iron Peak Lookout Tower, from which the magazine takes its name, the magazine engaged with local politics and tackled issues as diverse as environmental issues and countercultural philosophy. Over the years, following Livermore’s involvement with the Gilman Street Project in Berkeley and the punk-rock scene that loomed around it, Lookout’s focus shifted to music, which resulted in finding a whole new audience in the Bay Area and across the United States, especially among Maximum Rocknroll readers. -

Lookout #33 Lookout magazine started as a xeroxed community newsletter when Lawrence Livermore lived on Spy Rock, just a few miles north of Layonville, CA. Spy Rock was part of a constellation of locales across Mendocino and Humbdolt County that, since the late 1960s, had become increasingly popular among artists, hippies, and back-to-the-landers. Initially crafted in his solar-powered home, not far from the Iron Peak Lookout Tower, from which the magazine takes its name, the magazine engaged with local politics and tackled issues as diverse as environmental issues and countercultural philosophy. Over the years, following Livermore’s involvement with the Gilman Street Project in Berkeley and the punk-rock scene that loomed around it, Lookout’s focus shifted to music, which resulted in finding a whole new audience in the Bay Area and across the United States, especially among Maximum Rocknroll readers.

Lookout #33 Lookout magazine started as a xeroxed community newsletter when Lawrence Livermore lived on Spy Rock, just a few miles north of Layonville, CA. Spy Rock was part of a constellation of locales across Mendocino and Humbdolt County that, since the late 1960s, had become increasingly popular among artists, hippies, and back-to-the-landers. Initially crafted in his solar-powered home, not far from the Iron Peak Lookout Tower, from which the magazine takes its name, the magazine engaged with local politics and tackled issues as diverse as environmental issues and countercultural philosophy. Over the years, following Livermore’s involvement with the Gilman Street Project in Berkeley and the punk-rock scene that loomed around it, Lookout’s focus shifted to music, which resulted in finding a whole new audience in the Bay Area and across the United States, especially among Maximum Rocknroll readers.